In

the May-June, 1998 issue (Vol 40, #3) of the Astrological

Journal (published by the Astrological Association

of England) Theodor Landscheidt presents several

findings regarding the distribution of planets

in birth charts of famous people. One of his findings

is that the angular distance of Mars and Saturn

in the birth charst of 16,800 scientists and physicians

is more often in a golden ratio aspect than would

be expected by chance. Specifically, the following

angles were found to occur more often these charts

than would be expected by chance: 47.5, 55.6, 68.8,

85, 111.2, 137.5, 145.6, 158.8 and 175 degrees.

For an explanation of Landscheidt’s golden

ratio aspects, see the article at http://astrosoftware.com/Reassessment

of the Mars Effect.htm

Although

written over 12 years ago, there appears to be

little follow-up on this study. Landscheidt reports

that the data analyzed was gathered by Mulller

at the University of Cologne in Germany. I added

features to Sirius 1.2 astrology software to enable

me to obtain improved graphs from earlier versions

of Sirius to see how Mars-Saturn angles varied

from the expected distribution in six groups of

professional groups in the Gauquelin data: scientists,

musicians, writers, politicians, military leaders,

and painters. This data is included in Sirius and

I did not attempt to find out if the data collected

by Muller is available. If this data can be obtained

an reanalysis of Muller’s could be performed.

All

six professional groups in the Gauquelin data

have birth dates ranging from the 1790’s

or 1800’s to the 1920’ to 1940’s.

The Sirius software allows the user to produce

a distribution of a planetary angle over any

period of time to represent the random distribution

of the planetary period over that time period.

I found that the specific dates used had little

effect on the distribution as long as a range

of 100 or more years was used. I used a range

of 1800 to 1930 for this control group in the

analysis. Note that creating a control group

for astrological research is difficult in that

the definition of the population from which the

sample is collected is ambiguous given the uneven

and non-normal distribution of birth dates through

the time period. However, the full distribution

of Mars-Saturn angles for 130 years used represents

the likely distribution if births were equally

spread across this time period and given the

stability of this distribution and the deviations

with very small orbs found in this study as described

below, other definitions of a control group would

very likely produce very similar results.

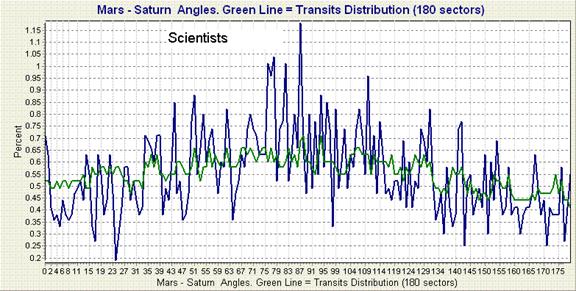

Shown below in Figure 1 is the random distribution

of Mars-Saturn angles the distribution of the

scientists in the Gauquelin data collection.

Angular distances are rounded to the nearest

degree from 1 to 180. The average percent of

charts at any degree is therefore 100/180, or

0.55. As expected from the much larger number

of charts in the random distribution, the random

distribution represented by the green line fluctuates

less than the distribution of scientists as represented

by the blue line. The random distribution is

based on 130 years x 365 days, or over 47,000

Mars-Saturn calculations.

Figure 1. Distribution of Mars-Saturn angles

in scientists and the random distribution.

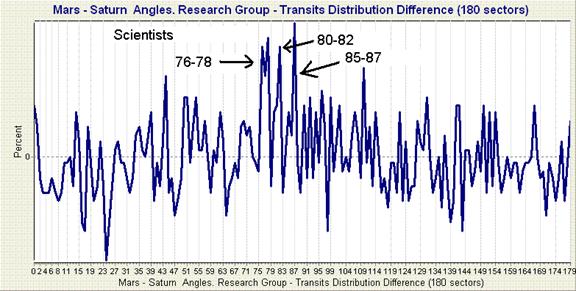

To visualize deviations from

the random distribution in another way, a graph

of the percent difference between the scientists

and the random distribution is shown in Figure

2 below.

Figure 2. Percent difference of Mars-Saturn angles

in scientists from a random distribution.

The

Sirius software also lists the values for each

degree so that the difference

at each degree is known. Referring to this list,

I noted the degrees that the graph in Figure

2 indicates that the Mars-Saturn angle occurs

more often for scientists than for the random

distribution. These angles are 76-78, 80-82,

and 85-87 degrees. In this exploratory phase

of research hard and fast rules are not used

to determine at which angular distances the scientists

and control group differ but salient peaks are

fairly clear. In general the findings do not

confirm Landscheidt’s finding. The peak

at 85 degrees is confirmed but overall the results

do not closely agree with Landscheidt’s

findings. Of the three peaks identified in the

graph, the peak at 76-78 degrees is most impressive

to me because the graph stays very high across

three degrees whereas the other two peaks extend

for only two degrees and are pronounced only

at a single degree. Note that in the line graph

angular distances vary from 0 to 179 so the range

of 76 to 78 degrees is actually a range of greater

than or equal 76 to less than 79 degrees. Interestingly,

a 3/14 aspect is 77.14 degrees and therefore

is approximately in the middle of this range.

In earlier research it was found that 14th harmonic

aspects involving Saturn are more likely in the

charts of scientists in the Gauquelin data (see

http://astrosoftware.com/DISCOVERY.HTM) . The

current findings suggest that it may be especially

the 3/14 aspect that is important for scientists.

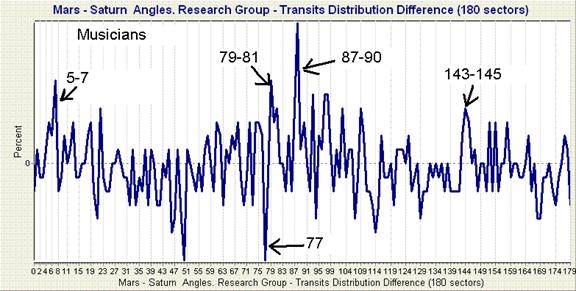

Shown in Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure

6, and Figure 7 are the percent difference in

the charts of the other five professional groups

in the Gauquelin data.

Figure 3. Percent difference of Mars-Saturn angles

in musicians from a random distribution.

Figure 4. Percent difference of Mars-Saturn angles

in writers and journalists from a random distribution.

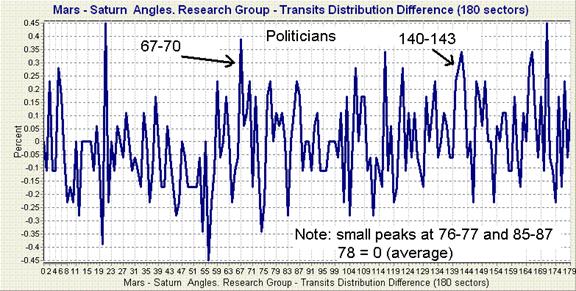

Figure 5. Percent difference of Mars-Saturn angles

in politicians from a random distribution.

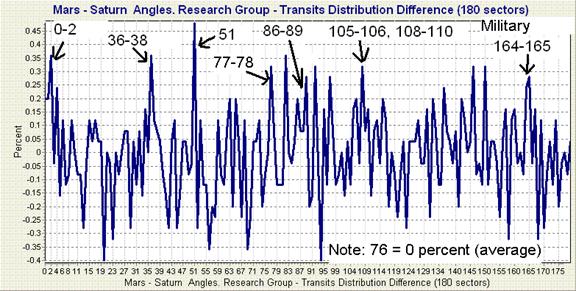

Figure 6. Percent difference of Mars-Saturn angles

in military leaders from a random distribution.

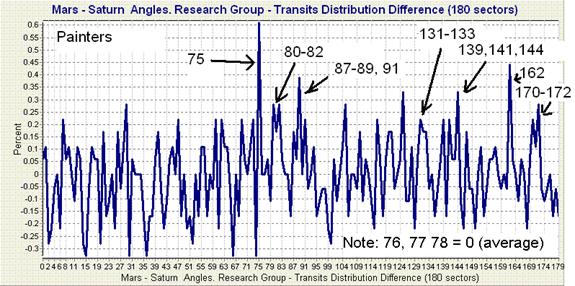

Figure 7. Percent difference of Mars-Saturn angles

in painters from a random distribution.

Interestingly, four of the six

professional groups have above average Mars-Saturn

angles in the 76-78 degree range, which as mentioned

above, is a 3/14 aspect. Painters have average

scores in this range, and musicians have a dramatic

decrease at 77 (which is 77 to 78 degrees), the

center of these 3 degrees. These findings are

difficult to interpret, but may be fairly consistent

with the early study of the Gauquelin data (http://astrosoftware.com/DISCOVERY.HTM)

which found that harmonics based on 11 occur

more often in the charts of musicians. The 11-based

harmonics are hypothesized to promote dynamic

movement and restlessness. Music may be a natural

outlet for people with this restless energy.

The 3/14 aspect might represent a quiet and focused

energy, almost a stillness. We can imagine children

who become very restless thinking about an algebra

problem and those who can focus on it very quietly

and intently. Nevertheless, achieving excellence

in music would presumably require great focus

of energies as well but the dynamic movement

involved in this concentrated activity may be

qualitatively different than in studying science,

for example. However, painters have an average

distribution of Mars-Saturn at the 3/14 aspect,

and one might imagine that painting would benefit

from concentration as well. In short, the findings

support the idea that some 14th harmonic aspects

are important in science, as found in the previous

study, and that the 3/14 aspect perhaps promotes

quiet and still focused concentration. However,

the findings are not unambiguous and may also

be random fluctuations that do not represent

a consistent astrological variable.

Other

researchers may be able to notice other interesting

details in these graphs. For the

present time I am content to conclude that this

study does not confirm the golden ratio aspects

but does suggest that particular angular relationships

based on harmonics may occur at measurable levels

in individuals whose behavior can be distinguished

from a random group. As Landscheidt pointed out,

if there is validity to the astrological proposition

that human behavior is associated with the angular

distance between planets, the angular relationship

is not likely to be in simple fractions of the

circle as as ½, 1/3. ¼, etc. as

most often used by astrologers.

A great amount of additional exploratory research

along these lines can be conducted. Using measurements

in right ascension and direct distance rather

than in zodiac longitude, heliocentric positions,

and the analysis of other planets besides Mars

and Saturn are among some of the most obvious

possible avenues for future research.

As

noted earlier, Landscheidt’s study,

despite the very promising findings which he

presents, appears to have remained dormant for

over a decade. Perhaps the lack of funding for

astrological research and a lack of motivation

and interest in this kind of research by astrologers

are contributing factors. I suggest that even

negative findings are important because the findings

provide information regarding the limits of astrological

information. At astrological conferences and

discussion groups many astrologers voice their

disinterest in scientific research in astrology,

but even if skeptics within the field of astrology

and outside the field of astrology are correct,

confirming to what extent astrology may produce

measurable results is an important contribution

to our understanding of a mysterious subject

that continues to be used and supported by a

great many people despite its status as a largely

fringe subject outside mainstream academia.

As often seems to be the case, the results

are intriguing but very far from a validation

of astrological principles. I conclude that if

astrology is capable of producing measurable

results, we have yet to identify a formula for

doing so and if a measurable effect of astrology

is found, it is not likely to conform to the

analytical procedures typically used by astrologers. |

![]() Copyright © Cosmic

Patterns. All Rights Reserved Created

Copyright © Cosmic

Patterns. All Rights Reserved Created